This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends Digital

Trends: The emerging digital spectrum, and the challenge of freemium

By Chris Cooke | Published on Tuesday 23 December 2014

The highly public debate initiated by Taylor Swift’s withdrawal from Spotify last month ultimately led to the usual chattering about what royalties, precisely, any one artist is earning from any one digital service as compared to another. But it also brought a much more interesting element of the digital music discussion to the fore. What should freemium look like? It’s an important question that will play a key role in how the digital market will mature in the next five years.

THE STORY SO FAR

If we take 1998 as the year when the potential of digital music first began to become apparent – the world wide web and MP3 having emerged earlier in the 1990s and the first few digital music start-ups, notably MP3.com and eMusic, having just launched – for much of the following decade the major music companies’ default response to most proposed digital business models seemed to be “no”.

Indeed, for the next five years major record company executives seemed to be in denial (digital would never go mainstream like the CD), or protectionist mood (CD sales must be protected from rising online piracy) or control freak mode (if digital music channels have potential, we should control those channels). Needless to say, none of these strategies worked.

During these first five years an assortment of digital music start-ups – mainly though not exclusively download-based – came to market, though few secured major label content (and some had only unsigned artists). But one player, Apple, managed to persuade or bully the majors to come on board, and so in 2003 the iTunes Store went live in the US. The majors insisted on digital rights management technology being added to Apple’s proprietary file format, but initially conceded to the IT giant’s one-price-fits-all 99-cents-per-download approach. Which looked good on a poster.

It’s fair to say, the iTunes Store worked. In fact, it really worked. Especially in the US and the UK. And for most of the next five years, when it came to new digital businesses, the majors said “yes” to anything that replicated iTunes, but remained resistant to anything else. Which was, in theory, good news to those with ambitions in the download space, though the continued insistence by the majors on DRM meant start-ups couldn’t sell MP3s, which meant their music wouldn’t work on the market-leading iPod, which made it all but impossible to succeed.

There were some exceptions to this “yes if you’re basically iTunes, no if you’re anything else” policy. The majors did license subscription-based download platforms, like the original legit Napster product, which operated much like the streaming services do on mobile today, though these never really took off.

And in the US, the majors were obliged by copyright law to license interactive radio services like Pandora, and through the Sound Exchange system where rates were set by a copyright court, so these did start to gain some momentum.

Plus some more innovative start-ups went with the “launch now license later” approach and subsequently scored major label deals, though said start-ups always risked being sued out of business if they couldn’t get the record companies on side.

But it was around about 2008 that you really sensed there was an attitude change at the major music firms. Maybe it was because more digitally savvy execs had reached positions of power. Or because digital channels had become such an important part of the labels’ marketing mix, digital at large was being embraced across the business.

Or perhaps it was simply because, after ten years of declining CD sales, the powers that be finally realised that making decisions based on propping up that one revenue stream was pointless.

Whatever, it seemed that from this point onwards, if presented with a new business model that heavily skewed away from or even competed with the iTunes approach, the start point for the majors became “maybe”.

Albeit “maybe” with a big proviso. “Maybe” providing you were a well funded start-up, tech giant or media firm able to pay significant upfront advances and, in the case of the new companies, willing to throw in a bit of equity assuring a big pay day if your business succeeded down the line.

But nevertheless, the shift to a default position of “maybe” was important and liberating. And you sensed that what the major record companies were basically saying circa 2008 was: “The future of this industry is digital, and likely not just iTunes digital, but we’ve no idea what this digital future looks like, so let’s do as many deals as we can, get as many experiments off the ground as we can, and screw as much upfront cash and equity as we can out of all our licensees, and hope that in ten years time something tangible and sustainable comes out of all of this”.

The big advances and equity have not been without controversy, of course. First, because the majors got them and the indies didn’t, though the creation of Merlin secured some parity for the independents.

Second, because artists are unlikely to get a share of any pay-back from the equity, and with many in the artist community already annoyed with the royalty splits they are being paid on streaming income and the secrecy surrounding the record industry’s digital deals, that’s going to be an issue when Spotify goes through with its IPO.

And there is an argument that, by insisting on big advances and equity, the labels have limited how many digital services can get to market, meaning some interesting start-up business models never got tested.

But all that said, there was a logic to the strategy the big record companies began employing towards the end of the last decade.

Let the tech and start-up community experiment, make as much money as you can during the experimental stage, cash in your shares from those few services that actually work, and let others take the risk over which digital platforms have legs. While the labels focus on their own risk management business, the risky business of investing in new recording artists and creating new content.

If we agree that the big rights owners changed their policy on digital innovations in 2008, and in doing so began a ten year experiment in 2009, then we’re now half way into that experimental decade. So where does it look like things are heading? And how, exactly, will freemium fit into the mix?

A DIGITAL MUSIC SPECTRUM

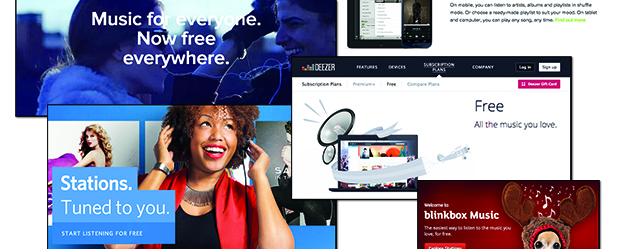

There are currently three main digital music business models: the iTunes style download store (the ‘ownership’ model), the Pandora-style interactive radio service (what digital music analyst Mark Mulligan calls the ‘listen’ model) and the Spotify-style on-demand service (the ‘access’ model).

Which of these three service types dominates varies greatly from market to market. The listen services are much more prolific in the US, mainly because – as previously mentioned – a compulsory license under American copyright law forced to the record companies to license the likes of Pandora early on at rates set by the copyright courts. Whereas in Europe the fully on-demand access services have enjoyed more success.

Though, it’s worth noting, while iTunes music sales seem to have peaked and are now declining, the ownership model is still the single biggest revenue generator in the US and UK. Whereas in Sweden and Norway, where iTunes-type downloading never really took off, on-demand streaming is already the biggest service type.

In terms of payment models, the download market is predominantly pay-as-you-go, in that you pay individually for each track you download, though some niche subscription-based download services do still exist.

In the streaming space there are ad-funded free options and then paid for options, with the standard premium rate set at ten pounds/dollars/euros a month (we’ll give all price points in dollars from this point). Though some services offer limited functionality packages at half that price and others a super-premium level for twenty dollars usually with high quality audio.

While there has been much debate over which of these service types and payment models will dominate long-term, it seems certain that what will eventually evolve over the next few years is a digital music spectrum, with a range of services that may incorporate ownership, listen and access elements. Crucially, across this spectrum there will be a number of different price points, with more variables between free and the current ten dollars a month standard.

Because one of the problems with the current streaming model is that the two main price points are free or ten dollars a month – ie free or $120 a year – which is quite a price jump. And while for music geeks at the labels and digital start-ups $120 a year for ad-free fully on-demand access from multiple devices to a catalogue of tracks in excess of 20 million seems like incredibly good value (which it is), spending $120 a year on music content seems like a massive commitment to the average consumer who maybe bought two or three CDs a year under the old model.

So while sign-ups to free subscription services have been impressive, and sign-up rates to some of the $10 a month premium services – most notably Spotify – are also encouraging, it is likely that a minority of consumers will ever commit to spend $120 a year on recorded music. Yet the options for those looking to spend $20-$60 a year are lacking, meaning those consumers are likely to just opt for freemium. And that group is much bigger than those currently buying into Spotify.

Everyone therefore agrees that, for streaming to go truly mainstream, we need additional price points between free and $10. Spotify has dabbled with a half price intermediary subscription in some territories, originally excluding mobile functionality, though mobile listening has become such the norm that a desktop-only paid-for service is becoming hard to sell.

Pandora’s premium option, being a listen rather than access service, is also pegged at $5 a month, though Pandora’s upsell of freemium to premium is nowhere near as impressive as Spotify’s (reportedly 5% of users pay, compared to Spotify’s 25%), suggesting that the majority see five dollars a month as being too expensive for mere personalised radio.

So what will this digital music spectrum look like? What variables can digital services employ to distinguish between different price points?

VARIABLES

The key question here is this: how can digital services, and especially streaming services, distinguish different ‘levels’ or ‘products’ in order to enable a range of price points?

Functionality: Listen v Access

The most obvious distinction to make is between the aforementioned Pandora-style ‘listen’ services versus the Spotify-style fully on-demand platforms. There is already a price differentiation here, in that Pandora premium is $5 a month whereas Spotify in the US is $10. Rdio currently provides listen with ads on freemium, fully on-demand on premium.

This price distinction is replicated in the royalties paid to rights owners. It’s been standard for sometime that it is cheaper to license a listen service than a fully on-demand access service. (As mentioned, in the US the former can be licensed via the compulsory licence administered by SoundExchange, so the rates are actually set by the copyright courts).

Within the listen level, there might be additional functional distinctions to make between freemium and premium, and different price points. The basic principle with listen is that users cannot pick and choose tracks on demand or listen to full albums. However users may be able to skip songs they don’t like, block certain tracks or artists from ever playing, or exert other controls over what music they listen to.

A service’s licence from the rights owners will usually limit what levels of functionality can be offered (in the US, too much functionality and a service will fall outside the SoundExchange licence), though where additional flexibility is available service providers could use those added functions to upsell to premium, or from one price point to the next.

Functionality: Devices

As mentioned above, at times Spotify has offered a half price subscription where listening is limited to desktop PCs, excluding mobile devices from the service entirely. More recently Spotify has only offered a listen service for freemium users on mobile, trying to entice people to pay for the full experience on their smartphone. And the new paid-for YouTube subscription service, currently in beta, will also be more mobile-friendly than the platform’s existing freemium set-up.

That said, with all the research showing that mobile listening dominates on most streaming services (especially if in-car listening is added into that set), there is an argument that while full mobile functionality can still be declined to freemium users (and therefore used to entice free users to start paying, as with Spotify at the moment), all and any paid-for packages need to be mobile friendly; ie users will begrudge paying even a few dollars a month if they find they can’t use the service on portable devices.

Navigation Tools

Everyone knows that navigating 20 million+ tracks is a challenge even for avid music fans and, indeed, the size of the average on-demand streaming service’s catalogue is arguably actively off-putting for more mainstream consumers, who probably only need access to a few thousand songs at most.

Which is why all streaming services have put so much effort into so called ‘discovery tools’ to help users navigate what’s on offer; a process which, ironically, sometimes involves users signing up to a fully on-demand access service but then using it as if it were a cheaper listen platform.

To date discovery tools have generally been used by streaming services to distinguish themselves from their competitors, rather than to set one price-point apart from another.

With most digital service providers (DSPs) offering a similar catalogue and similar functionality for a similar price, a key differentiator in the fledgling streaming music market has been “our discovery tools are better than their discovery tools” (even though its debatable if anyone has really cracked the discovery thing yet).

But the streaming platforms are yet to really say “look at our great discovery tools, you’ve got to pay a little extra for those”. Possibly because the mainstream consumers the DSPs are currently trying to hook in through freemium are exactly the sorts of people who need help with navigation, and if the discovery aids weren’t there from the start on the free level you’d never get them hooked enough to try and upsell premium.

Content Limitations

For a brief time when the fully on-demand services were first emerging there was some catalogue size bragging – “we’ve got three million more tracks than those guys” – though all the services now have such vast quantities of music the numbers all seem a bit meaningless.

Some services still brag that they are better at providing localised content for each country in which they operate, and there may be room in the market for bragging “we’ve got the best EDM, we’re the ones with all the 1980s pop or 1990s indie”. Though again, this is more likely a USP that can distinguish one service from another, rather than different price points.

Though some do believe that there could be a price point differentiation when it comes to new content; perhaps only top paying users get access to the latest releases. There has been a lot of talk about ‘windowing’ in the digital music space of late, whereby big name artists hold back new material from the streaming services, so that it’s only available on CD or for download for a time (sometimes weeks, though not uncommonly months).

As streaming becomes as big as CD and downloading in terms of users and revenue, this strategy – which, to be fair, is only currently operated by a small minority of big names – possibly becomes problematic (and some would say it already is). After all, ten-dollar-a-month subscribers are amongst the record industry’s best customers, and yet they are being penalised when it comes to new content.

But if the new content of bigger artists was to be held off freemium but made available to premium, that could work. Indeed, there are some windowing pop stars who would likely say they’d go that route in Spotify offered it (Swift’s label has only pulled her music from streaming services where ‘premium only’ isn’t an option for artists).

Spotify would likely argue that for that to work – ie for big new releases to be initially excluded from freemium – the rights owners would need to ensure their new content wasn’t available on user-upload platforms, and especially those that have a claim to being legitimate music services like YouTube, Soundcloud and, even, Grooveshark. Which is a good point and a challenge, more on which later.

Aside from new material, some wonder whether cheaper price points could be built around significantly smaller catalogues of music, given that the more mainstream consumers for whom ten dollar a month seems steep don’t likely need access to 20 million tracks anyway, nothing near that level in fact (indeed, as mentioned, such a large catalogue could actually be a turn off).

Amazon has been dabbling in this space with the music element to its Prime subscription service in the US, providing access to just over one million tracks, while the MusicQubed-powered O2 Tracks and MTV Trax services take the catalogue limitation thing to the extreme offering less than 100 songs at any one time (changing week-to-week).

Amazon’s limited catalogue still seems huge at first glance, though a less-money-for-less-tracks option possibly needs to offer more choice than the current MusicQubed options.

Content Exclusives

In his conclusion to our artist survey on all things digital that we conducted earlier this year, Dan Le Sac predicted that content exclusives will be part of the future streaming music market, with each streaming service offering exclusive new content from big name artists, and thus securing market differentiation Netflix style.

Does that mean the DSP becoming a label and commissioning (and paying for) a new record from a Coldplay, One Direction or Adele that would then only be available to its subscribers, in either the short or long term? Or the DSPs providing a major payment to an artists’ label partner to secure such exclusives?

While Apple is already doing such exclusivity deals in the short-term, it’s debatable whether such arrangements would become the norm in the streaming space, especially if the exclusive content was limited to premium users of a commissioning DSP. Many artists would be squeamish of forcing their fans to commit to $120 a year (or otherwise turn to illegal content sources) in order to have any chance of hearing their new material.

But the DSPs creating their own exclusive music-related content – live sessions, documentaries, festival coverage, guest mixes, seasonal compilations – seems more likely. A move that would basically shift the streaming services more into radio territory (and therefore a move the radio sector is already anticipating with some caution). In a related domain, as more mainstream consumers sign-up to subscription streaming services, expect celebrity-led programming to also come with premium.

Some streaming services are already dabbling in this area, and we will likely see much more of this in the coming years. And while much of this exclusive content will likely be used as a way to distinguish services initially – as Le Sac predicts – it could also be employed to separate price points.

Which would move the DSPs into a model akin to the satellite and cable TV networks: offer just enough extra exclusive content for another one or two dollars a month, and you will hook a certain portion of your subscribers into the next price bracket up. Indeed the DSPs could well adopt the language of the cable networks in communicating these packages.

Audio Quality

This is already being used by WiMP and Deezer to justify getting an additional ten dollars a month out of users (though in some markets they are only currently offering the high quality option, and in those territories it’s really about having a USP over rivals).

Now, the record industry has dabbled with selling recordings at a higher audio quality at a premium price for years now, in both the physical product and download space, with limited success. High quality audio disks remain very niche, even if those who do buy may be high spenders. While in the download space sales of WAV and FLAC files, where available, have been very limited.

But there is an argument that, in the streaming space, high quality audio could secure a bigger if still niche market. Even though many people are listening on devices not capable of delivering high quality audio, and even those who have the kit would likely struggle to spot the difference between a 320kbps MP3 and a CD quality WAV.

But the difference with high quality streaming – over similarly high quality disks or downloads – is that it doesn’t require consumers to invest in new technology, or be able to work out how to integrate FLAC files with their MP3 collection. The sell is therefore much simpler. Basically: “Pay us some more money, press this button, and listen to the music as if you were in the studio”.

It might just work, assuming there are no bandwidth problems, or capacity issues where offline listening requires a file to be downloaded to portable devices. WiMP for certain has been positive about the uptake to its premium premium offer since launching it last year.

A POSSIBLE SPECTRUM

So, there are a number of ways that the digital music providers, and especially the streaming companies, can play around with their products in order to create a digital music spectrum: differently priced packages for different consumers. But what will that spectrum look like in five years time, when this decade of experimentation is over? Well, it’s too soon to say of course, but possibly something like this…

Pay As You Go+

Some reckon freemium and premium listen and access services will ultimately replace ownership-based iTunes-style platforms; that the iTunes store isn’t just reaching a ceiling after a decade of rapid growth, but that it will now follow CD sales and move into a long-term period of decline, ultimately to disappear. Download stores were a temporary phenomenon as music consumption shifted from CDs to streaming, the argument goes.

But others think that a form of download platform will remain for the mid-to-long term. In that the most casual of music consumer will never fully embrace the access model, and would instead prefer to have a freemium radio style service to dip in and out of (somewhere between conventional radio and Pandora), but with the option to download for keeps (on a pay as you go basis) the handful of tracks that they really like each year. The radio element would be ad-funded or loss-leader, or possibly a combination of the two.

Whether this kind of casual music consumer exists below the age of 25 is debatable, though as the iTunes-style business model goes into decline this combo of radio-listen-download might take off for the foreseeable future, albeit servicing an older demographic. Indeed, that combo service maybe the next generation iTunes store, with Apple’s iTunes Radio set up and some elements of its new toy Beats Music better integrated with the download experience.

Of course stream-and-download combos have been tried before with little success. The radio industry tried including single track downloading into the digital radio experience, Spotify added ‘download’ buttons for a while, and some early streaming platforms included some MP3s for keeps in with their monthly price. But it’s possible that the early-adopters were never the right target audience for this kind of combined service, and there may be more potential for it as streaming goes fully mainstream.

Listen Freemium

While listen services may never have been as big in Europe as the US, it seems likely that Pandora-type set-ups do have a future, and could well become the primary way in which streaming music is offered on a freemium basis long-term.

Outside North America, it remains to be seen if this kind of streaming music service gains momentum via: new standalone services (a Pandora for Europe, a role Blinkbox Music currently plays in the UK); or by traditional radio stations moving into this domain as Spotify et al start to take a significant slice of the in-car listening market (ie as iHeart Radio is doing in the US); or by the subscription set-ups making their freemium options listen services (as Rdio has already, and as Spotify currently does on mobile).

For the music rights owners, listen services will always pay less than access platforms, and as this kind of service starts to compete with conventional radio for listeners and advertisers, listen service revenues could start to hit the royalties labels and publishers traditionally received from the radio sector. Though, because of reach and data, listen services do have the potential to get a much bigger cut of the advertiser pound overall than radio ever could, and the music industry will very much share in that.

Listen Premium (1-3 pounds/dollars/euros)

Premium listen services – offering ad free listening and extra functionality like track skipping and occasional full album streams – could be attractive to more mainstream consumers if the industry gets the right price point.

Pandora’s limited success rate in upgrading users from freemium to premium (especially when compared to Spotify’s rate) suggests that five dollars a month is too much for mere personalised radio. Could the DSPs and rights owners make this kind of service work for two dollars a month if appropriate market scale could be reached?

It may also be that its premium listen services that have the most potential to be absorbed by third-party resellers – ie tel cos, ISPs, cable companies or other content service providers.

The bundling of streaming music with other services clearly has a key role to play in future growth of the market (and, indeed,

has already played a key role in Spotify’s recent successes).

Though even with wholesale price discounting, a monthly price point in the region of ten dollars a month limits such bundling to more premium tel co / ISP / cable packages. A two dollar a month service is easier to absorb, and therefore has much more mainstream potential.

On-demand Economy (4-7)

Fully on-demand listening clearly demands a premium over and above personalised radio though – and the music community never wants to hear this – for mainstream consumers a leap to ten dollars is a leap too far. Consumers, therefore, need a middle ground on-demand service.

Cutting out mobile functionality – how Spotify previously enabled a half-price subscription – seems less and less viable as mobile listening becomes the norm. Therefore is seems that limiting access to content may be the way forward. Whether that be providing access to only a few hundred specially selected tracks (a model similar to O2 and MTV Trax), or a million mainly older tracks (the Amazon Prime approach), or leaving out content exclusives.

That said, even if the windowing of major new releases is to become the norm, holding big albums off freemium, it seems likely that said LPs would have to be made available to these economy subscribers too, to justify the switch from freemium to any paid-for level.

Therefore it may be that rather than content being taken away from economy users, additional exclusive content will need to be created for the next level up.

On-demand Premium (8-10)

Which brings us to a level akin to the current market standard price point (though, while the industry might be hoping this level can be subtly increased in price in the coming years, the opposite might actually occur as more players compete for market share).

This level will likely operate pretty much as Spotify, Deezer et al do at the moment, but with extra content to justify the higher price.

If this can’t be simply windowed new releases, then the DSPs will need to start creating and commissioning their own content series to justify full premium subscriptions, and this could well be where we see the most interesting developments in the digital space in the coming years.

On-demand Deluxe (15-20)

While we only have WiMP’s word for the fact that its super high quality premium premium package is pulling in consumers, the fact that it this year entered the UK and US markets operating with this model alone suggests that the company has some confidence that there is a market for high quality audio in return for higher subscriptions.

And for reasons outlined above, this high quality audio market – while likely niche – could end up being a much bigger niche than similar products in the physical and download domains.

And assuming that this audience are higher spenders and, very possibly, geeky early adopters, it may be that these premium premium users are also treated to the latest developments on the technical side, in both how and where streaming content is delivered.

THE PROBLEM OF THE FREEMIUM OF TODAY

And so, there we have the makings of a digital music spectrum for the future, which seems more or less workable, each level with a distinct relatively simple offer to satisfy the appetites of a different part of the market. But – bringing us right back to the Swift debate where we began – a question remains: Where does Spotify’s current freemium offer, let alone the main YouTube platform, fit into this mix?

The problem with Spotify’s current freemium option is that it’s arguably too good, with ad-free and fully-mobile-compliant the only two features held back from free users to entice them to sign up to ten dollars a month premium. And we can probably assume more mainstream users are happy to live with the ads, commercial radio listeners are certainly used to them.

With Spotify freemium users getting fully on-demand music on their desktops, a decent listen service on mobile, and access to Spotify’s full catalogue of over twenty million songs across all devices, it makes it very hard for other competitors to dabble with mid-range subscriptions. What can services offer to justify two or six dollars a month?

But Spotify’s current freemium/premium set up works. For Spotify.

And Spotify would argue that it’s working for the industry at large as well. Yes, Spotify freemium is a very good deal, hence the rapid sign-up rates in most territories. And yes, no one is really making much money out of freemium (rights owners are paid royalties, but a tenth of what they get from premium), but Spotify is turning a quarter of those loss leading users into ten dollar a month subscribers, a much higher up-sell rate than all of its competitors.

So, Spotify’s strategy does seem to work in getting the ten-dollar-a-month market established. But – and this is the problem – in doing so it is arguably hindering the six-dollar-a-month and two-dollar-a-month markets, which are likely to be much bigger in the long term. And that’s a pain if you’re trying to evolve that middle market.

Of course given the ten-dollar-a-month users are more likely to be early-adopters, it perhaps makes sense to prioritise getting them all signed up. But at what point do you put the focus on the middle market instead. Because at that point you’ll almost certainly need to turn Spotify freemium, in its current form, off.

There have been rumours, since the Swift spat, that the labels will try to force a cut back on Spotify freemium as their licensing deals with the service come up for renewal. Spotify will argue that it tried instigating limits on freemium before (eg a ten hours listening cap, a maximum number of plays per track), and that just hit freemium sign-up and usage rates in the territories where the limits were added, which in turn hit premium sign-ups.

Meddling with Spotify’s current strategy, therefore, simply hinders it success rate in getting ten-dollar-a-month subscribers. So let’s wait until they are all signed up, and then do something more dramatic to freemium in order to fuel mid-market subscriptions.

The labels may not want to wait, though as shareholders in Spotify – and therefore having a vested interest in the company having as high a value as possible at the point it floats – they may not want to rock the boat this side of an IPO. After that though, a rethink in freemium seems certain.

But even if the labels and DSPs did eventually move towards the model already employed by Rdio – listen for freemium and fully on-demand for ten dollars – what about the other sources of free content online? And even if, through web-blocking, the labels could limit prolific piracy to a relatively nominal minority, and then through more proactive takedown-notice issuing keep unofficial free streams off sites like SoundCloud, what about YouTube?

The problem with YouTube is that it’s an opt-out service and such an important marketing channel for the labels. No label wants to pull from YouTube, because they’d lose the marketing benefits, and the cut of ad revenue they earn, but would still have to invest time and money policing the site as users upload their content. Google exploits these facts to secure incredibly favourable risk-free royalty rates.

Spotify et al argue that the existence of YouTube is a hindrance for them signing up freemium users let alone premium customers, and that fact is only going to increase as the music and digital sectors focus on the potential mid-market subscribers.

Ideally for the digital spectrum to emerge YouTube also needs to take some features away from its freemium users: cracking down on ad-blocking for starters and possibly limiting some of its playlisting functionality. Quite how that would work isn’t clear; though it’s possible the labels hope that, as YouTube’s own premium set-up rolls out, the Google subsidiary will be more willing to consider such limitations.

And so, it seems certain that there is still plenty of change and debate and trial and error ahead as we enter the second half of the music industry’s big decade of digital experimentation. It’s not unreasonable to assume the pay off – something nearing a viable market in 2019 – can be reached, though some compromises will likely be needed along the way.