This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Artist News Business News Labels & Publishers Legal Top Stories

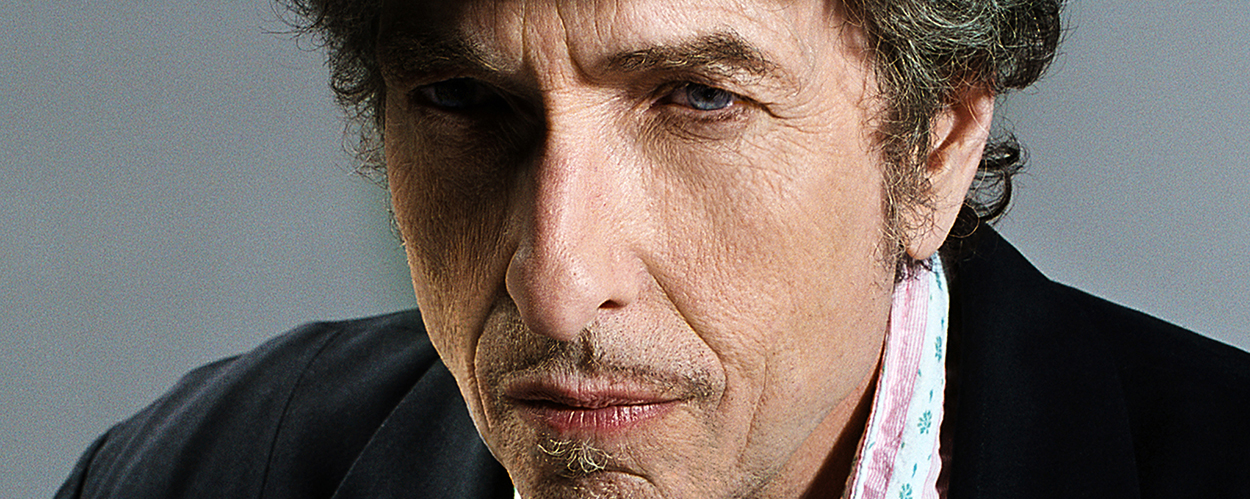

Bob Dylan urges court to uphold ruling in dispute with former collaborator’s estate

By Chris Cooke | Published on Monday 10 January 2022

Bob Dylan would like it to be known that judge Barry Ostrager was dead right when he dismissed a lawsuit filed by the estate of one of his former collaborators. And given just how dead right Ostrager undoubtedly was, why allow that estate to have a second go at grabbing a cut of Dylan’s big pay day from his 2020 Universal catalogue deal?

Jacques Levy collaborated with Dylan back in the 1970s, ultimately co-writing seven of the nine songs that appear on the 1976 album ‘Desire’. He also directed Dylan’s 1975 ‘Rolling Thunder Revue’ tour, which featured many of those ‘Desire’ songs.

Levy’s estate went legal after Dylan did that big deal with Universal Music Publishing, in which he sold his songs catalogue to the major for a reported $300 million. The estate argued that it was co-owner of the ‘Desire’ songs and should therefore get a cut of the Universal money in relation to those works.

However, when Levy and Dylan collaborated the former had a work-for-hire agreement with the latter. Under US law, that means Dylan owned the copyright in the songs they created together. While that agreement provided Levy with a share of any money generated by the songs, it didn’t give him co-ownership of the actual copyrights that were sold to Universal.

Also, while Dylan won’t be getting any future royalties from the major having taken that big up-front cheque, collaborators like Levy – due royalties under past deals with the musician – will continue to get their share of any future income that their songs generate.

But the estate argued that, while Levy’s agreement with Dylan was technically a work-for-hire arrangement, the deal was “highly atypical of a work-for-hire agreement, bestowing on plaintiff’s considerable significant material rights and material benefits that are not customarily granted to employees-for-hire and that the label ‘work-for-hire’ is, in this instance, a misnomer”.

However, judge Ostrager did not find those arguments compelling at all. Dismissing the Levy estate’s lawsuit last August, he said the 1970s agreement between Levy and Dylan was “clear and unambiguous” – and it was clearly and unambiguously a work-for-hire agreement.

The Levy estate is having another go at pursuing the action, having filed an appeal last November in which they accused Ostrager of citing inappropriate cases and ignoring critical information in his judgement.

But that’s just not true, legal reps for Dylan argue in a new legal filing submitted last week. Among other things, they stress that the Levy estate will continue to receive its share of any monies generated by the ‘Desire’ songs.

As such, the legal filing notes, “the only effect of the Universal sale is that the royalty checks to which plaintiffs are entitled will now come from Universal rather than from Dylan”. As a result, the Levy estate’s claim for cut of the Dylan’s big Universal cheque is an “impermissible double-dip”.

“They want both the continuing royalty payments from Universal and a piece of what Universal paid to buy out Dylan”, the lawyers go on. “It would be commercially unreasonable, grossly unfair, and downright absurd to pay plaintiffs their continued stream of royalty payments in addition to a share of the sale money when the only rights relinquished in the sale were Dylan’s, not plaintiffs”.

As for the estate’s interpretation of the 1970s agreement – both in its original lawsuit and since last August’s judgement – Team Dylan say: “Plaintiffs unleash a torrent of confusing, self-contradictory, and unpersuasive attacks on the trial court’s plain-language construction of the 1975 agreement”.

They go on: “Plaintiffs urge this court to use extrinsic evidence to override the 1975 agreement’s clear and unambiguous language, they reject fundamental canons of contract interpretation, and they advance a tortured reading that the text of the 1975 agreement does not support and that makes no commercial sense”.

In conclusion, Dylan’s filing states: “Plaintiffs are trying to rewrite the contract terms that have governed the parties’ relationship for nearly five decades. Plaintiffs reaped a million dollars in royalty payments under the 1975 agreement – a stream of income for them that will continue unabated long into the future following the sale to Universal”.

“Plaintiffs cannot change course and now deny the plain language of that agreement”, they add. Therefore the court should affirm Ostrager’s original judgement.