This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Artist News Business News Digital Labels & Publishers Legal Top Stories

Over The Rainbow writer’s estate kicks off a whole new mechanical royalties debate in a bombastic new lawsuit

By Chris Cooke | Published on Wednesday 22 May 2019

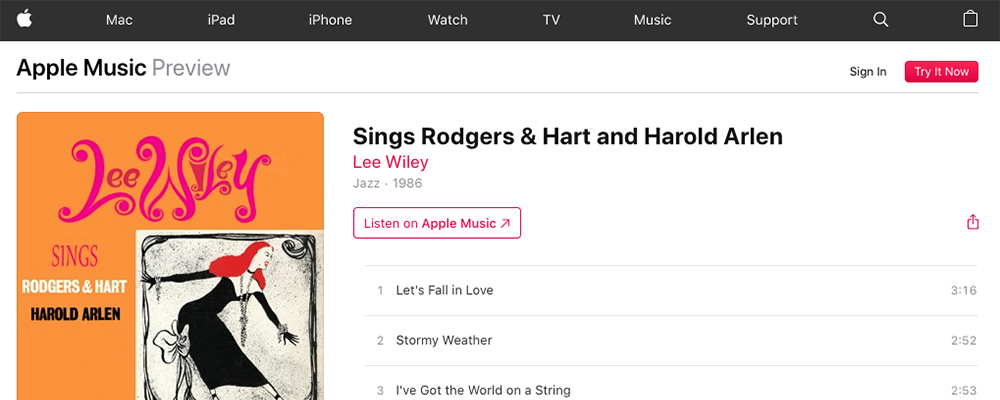

The son of Harold Arlen – the man who wrote ‘Over The Rainbow’, ‘I’ve Got The World On A String’ and ‘Get Happy’, among many other famous works – has sued Apple, Amazon, Google, Pandora and a stack of labels over allegations that they have all been involved in the rampant copyright infringement of his father’s songs.

The lawsuit was filed earlier this month and first reported on by Forbes, but we now know more about the litigation. At its heart it’s about digital music platforms distributing songs without having sorted out a mechanical rights licence, which might sound familiar, but this case is different to those that have gone before.

Nearly all the streaming services have been sued at some point in recent years in the US for failing to pay all of the mechanical royalties that are due on the songs they are streaming. In most cases, this failure to pay was mainly the result of the woefully inadequate licensing system operated by the American music publishing sector.

Technically a compulsory licence covers the mechanical rights in songs Stateside, so that the streaming services don’t need bespoke licences from each writer or publisher. However, they do need to send notices and payments to each rights owners of each song streamed for the compulsory licence to apply.

Because the streaming services don’t generally know what specific songs are contained in the recordings labels pump into their platforms – let alone who owns the rights in those songs – in some cases notices and payments were not sent. This meant the compulsory licence did not apply. Which meant the digital music firms were liable for copyright infringement. And so a flood of multi-million dollar lawsuits followed.

However, last year’s Music Modernization Act seeks to solve that particular problem. It basically stops the streaming services from being liable for infringement when the formalities of the compulsory licence are not fulfilled, in return for said services committing to fund the creation of a brand new collecting society. That which will then administrate mechanical royalties moving forward and, in theory at least, make sure writers and publishers get paid.

So what’s going on with this Arlen case? Well, in a long lawsuit that goes to great lengths to remind us just how great the composer was, lawyers for the music maker’s son and his company SA Music argue that in a plethora of cases where the tech giants have been distributing Arlen’s work, the compulsory licence doesn’t even apply.

Why? Because the sound recordings that contain the songs are not legit, in that the label or distributor that provided the tracks to the services does not own or control the original master recording. And if the sound recording is not legit, the compulsory licence doesn’t apply for the song contained within that illegitimate recording.

Arlen Junior’s lawsuit claims that while most of the famous recordings of his father’s songs are now in the control of major labels, there are numerous examples of independents also distributing those same tracks to the digital services.

Said indies could, of course, be doing this legitimately by having first acquired a licence to exploit the recordings from the relevant major, but the lawsuit claims that in most cases there are no records of any such licences being secured.

The lawsuit then states: “Upon information and beliefs, the pirate label defendants are simply duplicating pre-existing recordings made by others without permission, and joining with the distributor and online defendants to make digital phonorecord deliveries of the pirate copies of the recordings of the subject compositions in their stores and services”.

Although the tech firms are not directly involved in this initial (alleged) infringement, the lawsuit argues that they should still be held liable for it all. They profit from the unlicensed distribution of Arlen’s songs, says the legal filing. Also, they could and should control the reproduction and distribution of pirated music on their platforms.

Of course, if there are as many unlicensed versions of the most famous recordings of Arlen’s songs available on the digital platforms as this lawsuit suggests, you have to wonder why the labels that own those sound recordings haven’t also gone legal.

Though the case does raise questions about possible weaknesses in the digital supply chain in terms of filtering out unlicensed recordings. Which is something that has come up at various points in recent years, most often when random people have uploaded leaked versions of new music. In addition to that, Arlen’s legal filing also takes us back to the classic debate over the lack of a central music rights database through which digital services can confirm ownership, and the problems that can cause.

Arlen’s lawyers themselves say of their legal action: “This case is about massive music piracy operations in the digital music stores and streaming services of some of the largest tech companies in the world. Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Pandora and their distributors have joined with notorious music pirates to sell and stream thousands of pirated recordings embodying copyrighted works owned by SA Music and the Harold Arlen Trust”.

It will be interesting to see how this one plays out.