This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends

Trends: Catalogue marketing in the streaming age

By Chris Cooke | Published on Monday 25 June 2018

When the shift to digital really got underway with the opening of the iTunes store fifteen years ago, an assortment of new opportunities opened up for labels seeking to exploit their catalogues.

However, it’s with the shift to streaming that we have really seen labels seek to capitalise on these new opportunities. Partly because streaming brings with it even more opportunity. And partly out of necessity, because as more and more music consumers shift from sales to streams, the traditional approaches to monetising and marketing catalogue are becoming irrelevant.

Based on the new CMU Insights primer course on catalogue marketing recently launched as part of the BPI’s training programme, CMU Trends looks at the changes that are occurring.

We also talk to playlisters and marketers about the new approaches that are emerging, including: Alexis Metaoui, Head Of Catalogue at Believe; Chris Baughen, VP of Content & Format at Deezer; David Rowe, co-MD at Universal Music Catalogue; Joe Andrews, Director UK Digital Sales at The Orchard; Leigh Morgan, Global Head Of Trade Marketing at Believe; Tim Fraser-Harding, President Global Catalogue Recorded Music at Warner Music; Will Cooper, Director, Digital Distribution at BMG UK.

MAKING MONEY FROM CATALOGUE

Technically speaking, of course, a record company’s catalogue is every recording it currently owns or controls, and which it is therefore empowered to monetise. Although in the record industry the term ‘catalogue’ has generally been used to distinguish a label’s new and recent releases from everything that went before.

Quite at what point a new release ‘becomes catalogue’ is debatable. Though in most cases a label will consider an album or track ‘catalogue’ as soon as the A&R and marketing team that oversaw its initial release stop actively working on the record. At that point the music slips into the company’s catalogue and – instead of the frontline label that signed the artist seeking to drive sales – that job often falls to a separate ‘catalogue’ or ‘commercial’ team in the business.

It depends on the size of the record company of course, but that catalogue team is likely in charge of a massive amount of music. Therefore, for the majority of a company’s catalogue, the label is often pretty passive in the way it monetises these older recordings.

If a brand or film producer wants to syncronise a track to their video, or another label wants to feature it on a compilation, or another artist wants to sample it on their new record, then there is a deal to be done and money to be made. But in those scenarios the label is simply responding to interest from elsewhere.

However, for a portion of the catalogue, the label will be more proactive. That might involve going out and seeking sync deals rather than just waiting for them to come along on their own. Or a label might have its own compilation brands that can provide a new outlet for some of its catalogue.

For specific releases, especially in the CD domain, labels might play with price point, seeking a second round of sales from consumers who liked a record on release, but not enough to pay full price. Or who might be persuaded to impulse buy a record during a high street retailer’s sale.

Of course, there are also the classic catalogue products labels traditionally produced around their biggest releases and most successful artists: the special edition, the re-issue, the remaster, the HD audio release and the limited edition box set.

In the main labels treated these reworked versions of old albums as if they were new releases and marketed them in much the same way as a new record, with a three to four month campaign including press, promotions, advertising and, in more recent years, a load of social and digital activity too.

Arguably, an assortment of new opportunities for exploiting catalogue came about when the iTunes store opened for business, simply because digital music is always in stock. In the physical space exploiting catalogue came with the risk and hassle of pressing more CDs, distributing and storing that product, and persuading retailers to give catalogue albums shelf space. But once a track or album was on Apple’s server in was on the virtual shelf forever. Exploiting catalogue involved less heavy lifting.

That said, the iTunes store was, in essence, simply a digital version of the record shop. Which meant that the traditional tactics for exploiting catalogue still worked. So the compilations, special editions, re-issues, remasters and limited edition box sets continued to be released, usually alongside physical versions, the record industry still being in flux and many catalogue customers still buying compact discs.

Then began the shift to streams. This resulted in two things. First, the old re-release products started to feel irrelevant and old hat. Secondly, with streaming comes another big opportunity. No longer is a label asking a fan to specifically put his or her hand in their pocket in order to generate new income from catalogue. Instead labels simple need to persuade said fans to press play. Albeit a lot.

With the shift to streams also comes consumption trends that justify labels putting ever more effort into catalogue marketing. BPI analysis of Official Charts Company data in 2017 showed that as consumption shifts from CD to downloads to streams, the amount of catalogue music being consumed increases. So whereas with CD the majority of sales are of records released in the last two years, with streaming the majority of streams are of tracks released more than two years ago.

Hence the enthusiasm at the labels to step up and re-evaluate their catalogue marketing activity. As David Rowe at Universal Music Catalogue, says: “There will always be work to be done to digitise legacy recordings, but current levels of availability are unprecedented. This brings with it the chance to join the dots between different artist catalogues and inspire people to listen to music they have never experienced before”.

DO TRADITIONAL PRODUCTS WORK?

As with everything in the modern record industry, capitalising on the new opportunities means employing new approaches and creating new products. But you can’t immediately drop the old approaches or the old products either. That is as true in catalogue as anywhere.

While streaming is driving all the growth, downloads and CDs continue to generate income in many markets, and so traditional catalogue strategies like playing with price point and re-issue campaigns still have a role to play, especially with older catalogue that is likely of primary interest to older consumers. When it comes to streaming, playing with price point is no longer an option, and re-issue campaigns are no longer necessary.

Long-term, as physical – whether CD or vinyl – becomes more of a premium than mainstream product, re-issue campaigns may live on, but probably more as part of the direct-to-fan business rather than traditional music retail.

It feels like the music industry at large is still to truly capitalise on the direct-to-fan e-commerce channels now available to artists and their business partners. Indeed, for a time labels often saw direct-to-fan as a threat rather than an opportunity, in that it might allow artists to sell their recorded music without a label partner. In fact, direct-to-fan is a big opportunity for labels to sell premium products direct to an artist’s fanbase, and this is particularly true for premium products that utilise catalogue recordings.

These opportunities may be realised by labels establishing their own direct-to-fan stores, utlising platforms like Music Glue and Pledge Music. Or by labels tapping into their artists’ D2F channels. This basically means treating artists as retailer partners, securing an artist’s buy-in by offering them the retailer’s cut in addition to any royalties that are due on the sale. A combination of the two approaches is probably most desirable.

While the potential of direct-to-fan in the catalogue domain should not be underestimated – and realising that potential may require old school reissues and box sets – when it comes to capitalising on the opportunities created by the big shift to streaming, a new approach is required.

Leigh Morgan, Believe: “The focus used to be on price dropping operations around key catalogue titles and/or recompiling catalogue in to compilations. With the significant decrease in downloads and the advent of streaming, the focus has shifted away from those type of operations to curation, track pitching and creative content operations aimed at driving streams”.

Will Cooper, BMG UK: “Streaming has led to a move away from overly rigid release schedules and only promoting and pushing an artist around the release of new products. Artists need to be ‘always on’ if they are to grow their streams. This doesn’t just mean releasing new tracks, but also includes a planned approach to digital marketing and trying to drive interest in an artist through their social channels”.

CREATING A BUZZ THROUGH CONTENT

In the streaming business, success is all about driving repeat plays and sustained listening- ie persuading fans to revisit music again and again. The royalties generated by any one play are nominal, but over time that revenue builds and builds. Achieving repeat listening means finding new reasons to connect to fans – through social channels, online media and elsewhere – and providing reasons why they might want to talk about, search out, share and play old tracks once again.

As we’ve mentioned, in the streaming age catalogue marketing is no longer about creating new product, it is about creating new interest in existing product. Which means labels need to find new reasons why old tracks feel timely again without being able to rely on an actual reissue as a hook. What are you going to do to make an artist, album or track feel ‘of the moment’?

David Rowe, Universal Music Catalogue: “The best catalogue marketing presents music to fans in a different and refreshing way. These types of projects may not manifest themselves in the form of a traditional ‘product’ on a streaming platform but those principles remain the same”.

A simple solution is to create some new content around the artist or the record. Content creation has become a big part of music marketing at large in recent years, despite the fact that the record industry’s core product is, in itself, content. Creating content for marketing purposes usually means creating something visual – photography, animated GIFs and/or videos – which uses or explores a track and which is shared and promoted across the social networks and pitched to online media.

Most labels are now employing this tactic to keep new music in people’s feeds and minds for longer, to encourage repeat listening on the streaming platforms in the months after initial release. As catalogue marketing evolves, this kind of marketing content is becoming key for driving streams of older tracks too.

Alexis Metaoui, Believe: “Why should we focus content creation on frontline release? Should we not think about content creation around catalogue? If you create content around a track, or a release, from videos to events, you can create interest”.

Will Cooper, BMG UK: “Unreleased tracks, remixes, memes, GIFs, interviews and announcements can all help re-invigorate interest”.

Quite what kind of content a label is creating around catalogue will vary according to the music and the budget, and whether the artist is actively involved in the project. A good starting point is delving into a label’s archives to see if there is any visual content that could be reused and repurposed to create new interest on the social networks and at online media. Clever use of archive materials need not be expensive, and then more effort can be put into the distribution and communication of the content.

Beyond the archives, labels need to get creative and think of compelling ways to represent artists, albums and tracks, that add to what went before. It may be possible to involve media or other partners in this process, which may bring new ideas or options to the table, as well as providing other ways to distribute resulting material.

Obviously it helps a great deal if an artist is involved in this activity, as they will have a more direct connection to their fanbase via social and can appear in any new videos. Where a label is no longer actively working with an artist, it may need to persuade said artist to get involved. Maybe the artist has their own projects to promote, and a joint effort can help achieve their marketing objectives, as well as driving more streams.

Whether or not the artist is involved, a label will also need to consider where else it can push this new content so to reach the right audience. What social channels? What media? What other channels does the label have? And are there any other partnerships that could be struck up to get the new content out further?

And don’t forget, the new content should come with a clear ‘call to action’ that drives new listening of spotlighted recordings on a fan’s streaming platform of choice. The label needs to make it as easy as possible to find and stream featured tracks. Which might involve the artist or label setting up a playlist on each of the key platforms. Which, in turn, brings us to playlists!

PLAYLIST PITCHING

We know that in the streaming domain, playlists increasingly drive listening. Users rely on public playlists to discover new music and rediscover old favourites, and then personal playlists in their own library to allow easy access to the music they know they love.

While there are lots of public playlists curated by labels, media and other opinion formers, by far the most influential playlists are those controlled by the streaming services themselves. Which is why – when it comes to the marketing of new releases – labels now put a huge effort into pitching tracks to the curators of the playlists at the key streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple and Deezer.

Playlist pitching of this kind has quickly become a staple of music marketing at frontline labels. But what about catalogue?

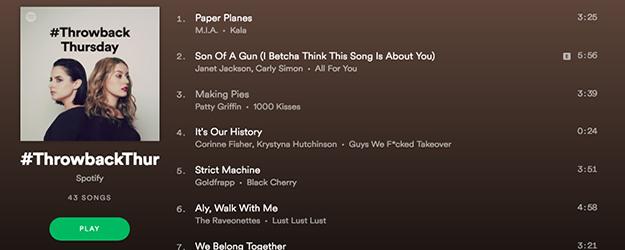

While many of the biggest playlists on the streaming platforms are focused on new music, there are nevertheless significant playlists that also feature catalogue. Some playlists are exclusively focused on older tracks – such as decade-based playlists and ‘old school’, ‘throwback’ and ‘classic’ playlists – while others mix catalogue in with newer releases. As with the big new music playlists, these all have curators.

Alexis Metaoui, Believe: “Many playlists are adding more and more catalogue to their tracklisting. Lots of mood playlist have been reworked to incorporate catalogue”.

Whereas the playlist pitching activity of labels used to be very much focused on new releases and therefore the new music playlists, more recently we have started to see catalogue marketers also pitching into the people who curate catalogue playlists. Some playlist curators are resistant to overt pitching at first, but usually come to accept it and then expect it. Which seems to have happened with the catalogue playlist curators.

Chris Baughen, Deezer: “We are seeing a rise in pitches for catalogue artists as this is an area that, until recently, has remained relatively unexploited”.

However, with so much catalogue available to be pitched, and a small number of curators in charge of a relatively small portfolio of catalogue-centric playlists, this pitching needs to be focused. The feedback from the curators is that catalogue pitches need to tick three boxes. First, they need to be super relevant to a target playlist. Secondly, there should be a reason why an old track is timely again. And third, there should be some activity planned beyond the streaming service to back up the inclusion.

Super Relevant

To be super relevant, marketers pitching tracks to curators need to listen closely to any playlists they are targeting and be honest with themselves: can you really hear your track in that playlist? Some playlists seem to cover entire genres by their name, but actually may skew to specific sub-genres within that domain. So you need to make your pitch relevant not to the playlist’s title, but to the music featured on it.

Joe Andrews, The Orchard: “The first and most important point as always is to find playlists relevant to your material and listen to the playlists yourself to realistically gauge if it would fit. A classic alternative rock playlist won’t be a comprehensive overview of every type of alternative rock track, it will most likely reflect a sound, time or scene within that genre and the relevance of your track will depend on that”.

Most catalogue playlists on the streaming services are about ‘forgotten favourites’. Which is to say, they are not there to put the spotlight on older recordings that didn’t get the attention they deserved first time round. It’s more about reminding subscribers of tracks they loved in the past but have totally forgotten about.

Which means that in most cases labels should be prioritising catalogue tracks that enjoyed some success on original release. And therefore, a good starting point in this process might be identifying which tracks in the catalogue fit this criteria.

Joe Andrews, The Orchard: “If you think you have key music that relates directly to the sound of a playlist and its not represented then it could be worth highlighting but only if it matches the size and status of the artists and tracks already included. Spotify are focused on serving up a compelling experience of important tracks with these types of playlists, rather than the discovery of fringe releases or album tracks. If your tracks don’t fall into that, don’t expect to be included”.

It’s also worth noting, that – with the exception of the decade-specific brands – many catalogue playlists on the streaming platforms skew towards music released since 2000. That may be representative of the age of the average streaming platform subscriber. Or possibly the age of the average streaming platform playlister.

However, as subscriber numbers continue to grow, we can expect streaming platforms to dig deeper into the catalogue. It may also be that certain services tend to do this more than others. With Amazon targeting a more mainstream and possibly older consumer, it seems likely that it will ultimately feature much more pre-2000 music in its playlists.

Timely

Many playlisters say they most like being pitched catalogue tracks when there is something that makes an artist or a specific record timely again.

This is quite straightforward. It may be as simple as a key anniversary occurring or sales landmark being passed. It may be that an artist has new activity, such as tours, festival slots or other projects. It may be that a track is back in circulation thanks to a sync. Or it maybe that an artist or a track fits into a wider event, like Valentines Day, or Christmas, or the World Cup, or a major talking point of the moment.

Chris Baughen, Deezer: “As we continue to look for new ways to editorialise our extensive collection of songs, there are many opportunities around moments such as anniversaries, birthdays, deaths, tours, events and seasonality that give great reasons to highlight this content. We would encourage labels to be thinking of editorial ideas around their catalogue and to pitch these as much as possible”.

Tim Fraser-Harding, Warner Music: “We secured a sync deal for Led Zeppelin’s ‘Immigrant Song’ that saw it used in the trailer for the ‘Thor: Ragnarok’ movie. We used that placement to drive interest on streaming services in the song, including pitching it to Spotify’s Rock Classics playlist, as well as the band’s broader catalogue”.

The fact that the timeliness of a track increases the likelihood that a pitch will work helps labels with the tricky of task of deciding which artists, albums and tracks in its catalogue to prioritise at any one time.

Truly capitalising on all this possibly requires labels to first review their catalogue and then log dates, events and stories attached to each album and track, so they know if and when those albums and tracks are likely to become timely again.

Activity

Streaming services are much more likely to put the spotlight on catalogue music if a label is likewise planning some activity around the album or track.

Which simply means pitching should be in sync with other catalogue marketing activity, such as the original content approaches discussed above. When pitching tracks to the services, labels should be clear about any activity that is planned, explaining when and where new marketing content will be pushed.

Tim Fraser-Harding, Warner Music: “It’s worth pitching music to [catalogue playlists] provided that we have a good reason for doing so and an appropriate marketing plan to support the track concerned”.

AN EVER EVOLVING BUSINESS

Music marketing across the board is evolving rapidly with the shift to streams. Many of the changes occurring apply to catalogue as much as new releases, though often with some extra challenges thrown in.

However, as we’ve seen, there are many exciting opportunities to drive new streams and new revenues around catalogue, and by employing new content and playlist centric approaches, labels could be delivering much more value from catalogue than in the past.