This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends Digital Labels & Publishers

Trends: Five key digital challenges for the music industry in 2016

By Chris Cooke | Published on Wednesday 23 December 2015

The key trend in the recorded music market this year replicated that of 2014: CD sales continued to decline, download sales declined a lot, and streaming income boomed.

The big debates around digital music were also pretty familiar: royalties, freemium and YouTube. Though the publishers and songwriters became more vocal in the royalties debate; some of the labels that had previously embraced Spotify’s freemium-to-sell-premium approach started to become critical of it; and the YouTube hate that emerged in the music community in 2014 evolved into a campaign to reform the ‘safe harbours’ in copyright law which the video site exploits.

In terms of the streaming services available, several operators disappeared from the market, while we had one big new entrant in the form of Apple Music. Though it is offering pretty much the same product as Spotify and Deezer. Even though the one thing many commentators agreed on this year is that what the streaming market really needs is more variety; because the truth is, the £120-a-year all-you-can-eat set-up is not attractive to mainstream consumers.

Which means that, despite Spotify founder Daniel Ek insisting his service was now “mainstreaming”, it is still early-days for the streaming sector. Spotify may be cornering the £120-a-year all-you-can-eat niche – with Apple Music already in second place – but when it comes to the much bigger mainstream market, it is still all to play for. Though Amazon and YouTube – and, in the US, Pandora and iHeartRadio – probably have the head start.

As we head into 2016, what are the five biggest digital challenges facing the music industry?

1. SOLVING THE ‘DIGITAL PIE’ DISPUTE

This was certainly the most lively debate at CMU Insights @ The Great Escape back in May, though the digital pie is still being sliced pretty much the same way as it was this time last year. What we are talking about here is how the monies generated by streaming are split between the digital service providers (or DSPs) themselves and the record labels, music publishers, recording artists and songwriters.

Although rights owners will usually put ‘minima’ into their agreements with DSPs – which mean they are assured minimum per-stream payments – ultimately most streaming deals are revenue share arrangements. Given that streaming services cannot afford to be loss-making ventures forever, the DSPs need to get to the point where revenue share arrangements outperform the minimum guarantees, because while minimum rates are being paid they are basically subsidising the music industry.

Every rights owner reaches its own revenue share arrangement with each DSP, and the specifics of those deals are secret. Still, we know that labels are taking 55-60% of the DSP’s post-tax revenue, while the publishers (directly or via their collective management organisations, or CMOs) will be taking 10-15%. Overall the DSPs are seeking to keep about 30% of revenue.

The label receives so much more than the publisher primarily for legacy reasons. The label always kept the majority of CD income, because of the costs it incurred in producing new recordings, and manufacturing and distributing the discs. And that model was basically transferred over to digital. Publishers receive slightly more from downloads than CDs, and slightly more from streams than downloads, but the label still sees the lion’s share.

Publishers have started to question whether that is fair, asking if labels make quite the same investment with streams as they did with CDs. While there may not be a case for having a 50/50 split between labels and publishers – which is more or less how it works with radio income in the UK – some feel the publishers should still be getting a bigger slice of the digital pie.

The big question is how can that be achieved? With CDs, the label pays the publisher its share of revenue, so the publisher and label can in theory negotiate splits (though compulsory or collective licensing rules may get in the way). With streams, the publisher has its own direct relationship with the DSP, rather than dealing with the label. It can ask for more money from the streaming service, and some have, but the DSP will insist that it needs its an approx 30% split to be a viable business, and up to 60% of its revenue is already committed to the labels.

Which means publishers ultimately need to sort this out with the record companies. Many publishers (and all three majors) are in common ownership with a label of course, so that might seem like an easy thing to achieve. Though because record deals are conventionally stacked in the label’s favour, whereas publishing deals pay the majority of income to the songwriter, businesses that deal in both recording and song copyrights will prefer the status quo.

The battle must be fought, therefore, by standalone independent publishers and/or the songwriters themselves. Both have been criticising digital royalties this year, though they have sometimes criticised the DSPs more than the record companies. Will that change in 2016? Don’t hold your breath. Though if the world’s biggest music publisher – Sony/ATV – was to be sold by Sony, and there’s an outside chance it might be, then it could potentially lead on this push for a re-slicing of the digital pie.

Beyond the recordings/publishing split is the debate over how monies are shared between labels and artists, and publishers and songwriters. The former is more contentious, because publishing deals tend to be at least 50/50 arrangements, or more likely tipped in the songwriter’s favour, whereas many record deals allow labels to keep the vast majority of core revenue streams.

There are various strands to the label/artist digital royalties dispute, especially with heritage acts who are still earning from legacy contracts that don’t specifically reference download or streaming income. There is the ‘sales v licence’ contractual interpretation dispute which, although partly settled in the US this year, is still a feature of some outstanding litigation.

There is the debate over whether or not labels actually need new permission from legacy acts to digitally exploit their recordings, because doing so arguably exploits an element of copyright called ‘making available’ that didn’t exist before the mid-1990s, and is therefore not mentioned in old record contracts.

And there is the debate over whether or not streaming actually does exploit ‘making available’, because if it doesn’t, it exploits the ‘communication’ element of the copyright where artists are due an automatic 50% revenue share under the principle of ‘equitable remuneration’.

We consider the latter two strands in more detail in our trends article on ‘making available’ in this edition of the Trends Report. For now, what we know for certain, is that all elements of the digital pie debate will continue in 2016. Though the labels will be hoping that they can keep the debates just rumbling on until the digital pie is so big, those taking smaller slices will still get their fill, and shut up about the splits.

2. GETTING BETTER AT PROCESSING THE MONEY

We know that many labels, publishers and CMOs have struggled in recent years to cope with the ever-increasing amounts of data that they have had to process as the record industry has shifted from sales to streams, so that DSPs report every time a track or song is played, not just the initial sale. This challenge only increases as key streaming services increase their user-bases, and reports from the streaming platforms become ever bigger each month.

Record companies need to ensure that they have received the right royalty payments from each DSP based on each service’s consumption reports. They then need to work out what is owed to any featured artists, producers and other parties who are beneficiaries of recordings in their catalogues, and then report and pay those royalties.

Publishers – and/or their societies – have an extra task to handle. DSPs assume that when a label or distributor provides a track, it owns or represents the sound recording copyright in that recording, and therefore pays the label when that track is consumed. But the DSP doesn’t know who controls the accompanying song copyright. So it provides each publisher and publishing CMO with a complete report of all songs played in any one month. The rights owner or society must then work out, of those songs played, which it owns or co-owns, and invoice accordingly.

Like the label, it must then work out what cut of the income needs to be shared with the songwriter. Again, there is an extra layer of complexity here in publishing, because a stream exploits both the ‘mechanical’ and the ‘performing right’ elements of the copyright (the latter being – technically speaking – the aforementioned ‘making available’ right).

This is important because mechanical and performing rights have traditionally been managed differently in music publishing. So, in the UK, mechanical rights income is paid to the publisher (either directly by the DSP, or via collecting society MCPS), which then shares a cut of that money with the songwriter, according to the terms in their publishing contract. But performing rights income goes to PRS, which pays 50% direct to songwriter and 50% to publisher, which might then have to share some of its half with the songwriter, according to the terms in their publishing contract.

So, even once a publisher or society has worked out what it is due from the DSP, it must then split that money between the mechanical and performing right elements of the copyright (the split varies from country to country). UK songwriters will then receive their share of mechanicals from their publishers, 50% of performing rights income from PRS, and probably a top up of performing rights income from their publishers too. Basically, it’s rather complex.

Most labels, publishers and CMOs have now developed technology platforms – or have engaged the services of distributors or rights administrators with such technology – to more efficiently process the data provided by the streaming services each month, and to work out what money they are due and what needs to happen to that income. Needless to say, some of these platforms are better than others.

Challenges still remain. Most companies are still evolving their data systems, especially when it comes to how they report usage and royalties to other parties, ie their artists or songwriters. And even where decent data systems have been built, there remains work to be done on helping artists and songwriters – and their managers and accountants – navigate that data.

Plus, of course, the lack of transparency over the fundamentals of the deals between labels, publishers, CMOs and the DSPs make it impossible for artists and songwriters to truly audit the information their business partners provide.

Things would be simplified, of course, if there was a central database of music rights ownership information – listing who controls and benefits from each song and recording – and via which DSPs could automate more of the process. Everyone agrees such a database is needed, but few agree on how it should be created, who should pay for it, and who should hand over their data to make it happen.

In his interview with CMU, Bruno Guez of music data firm Revelator reckons a start-up is more likely to solve this problem than the industry itself, possibly by building a database on the blockchain. But that start-up would still need access to source data, and that is probably the biggest challenge, given rights owners are often nervous of publishing the specifics about what songs or recordings they own or control.

3. DRIVING SUSTAINED LISTENING

Most music marketing is led by labels, and most marketing campaigns are built around album releases, and those campaigns usually aim to ensure maximum hype around launch in a bid to achieve maximum sales in the month or months immediately after release. Within a few months (maybe a few weeks even) of release, the label will stand down its marketers, who will begin work on the next record.

As we shift ever more towards the streaming model, success in the first few weeks after release is not going to bring in enough money for any of the stakeholders, and especially those on a small cut of the income (basically everyone but the label). The goal, therefore, is no longer ‘first week sales’ but ‘sustained listening’, meaning the message of the campaign is no long “buy me” but “playlist me”.

There has been much talk this year of the importance of playlists on the streaming platforms – and especially on Spotify – with labels putting increased effort into pitching new tracks to those who control playlists on the streaming services.

Anyone can set up a playlist on Spotify and make it publicly available, and anyone who does so – and somehow finds a following – is now likely being PRed in the same way as radio programmers. Though most of the biggest playlists on Spotify are controlled by the DSP itself, making access to its team of curators all the more important for the music community. Some label-controlled playlists have also built sizable audiences, and record companies large and small have been putting more effort into this of late as well.

There are different elements to the big playlisting pitch party. Getting added to public playlists with decent followings is a great way to get new artists and tracks onto the radars of streamers, and can assure short-term listening and therefore short-term revenue.

For sustained listening, labels probably need users to start adding their tracks to their own personal playlists, and especially those they come back to time and again: the work playlist, the gym playlist, the late night playlist, the long drive playlist, and so on. And that might require changing the messaging across an album’s marketing and PR campaign.

It may also require marketing campaigns that go beyond the traditional twelve-week album launch. But are labels structured and resourced to do that? If the marketing of any one artist is going to become a year-round venture, should management lead? Does management have the resource? Could labels be incentivised to change their approach to artist marketing by being cut into other revenue streams via multi-stream record deals? So many questions.

With streaming set to become the dominant recorded music product, music marketing is in flux. Though what is required for sustained listening on the streaming platforms may be the same as what is required to fully capitalise on the opportunities of direct-to-fan, and if labels can build a new marketing machine capable of delivering for both – and then sign-up artists to deals that mean they benefit from both streams and D2F – there could be a winning formula somewhere out there.

4. CONVERTING FREEMIUM

We all know that there are many, many more people accessing free streaming services than the paid-for platforms. We also know that the monies generated for the music industry by free services – both per-play and per-user – are much smaller than with the premium set-ups. Which means a minority of avid music fans are subsidising the listening of the more mainstream majority. Plenty of people in music don’t like that fact.

Though it is worth noting that that phenomenon is not actually new. Prior to digital, a minority of consumers regularly bought CDs, while the vast majority consumed music primarily through free-to-access radio services, which paid nominal royalties to the music rights sector. The difference now, of course, is that the services enjoyed by the paying minority are not so different to those enjoyed by the free-ride majority.

Either way, there is increasing resentment to the free-to-access services within the music community, even if artists, labels, songwriters and publishers can’t actually cut off the freebie platforms, for various reasons. But the free services could and should evolve. Quite how depends on what purpose, exactly, the free streaming services play in the wider scheme of things: are they marketing channels, revenue streams or up-sell platforms, and if the latter, what are we up-selling?

The labels always accepted relatively low royalties from radio (or tolerated no royalties from US radio) because they knew airplay was an important marketing tool. In the digital age, YouTube also sits in this domain. Everyone agrees YouTube is a vital marketing channel for most artists today, and Google has arguably exploited that fact to secure preferential rates from the music industry.

But marketing what to whom, exactly? If the average young YouTube viewer is never going to buy an album – or even pay for a Spotify subscription – while they have all the music they want on-demand via YouTube itself (which seems likely), what is the aim of the marketing effort? Tickets, merchandise, direct-to-fan perhaps?

Though the label – which maybe doing most of the heavy lifting in terms of feeding and managing the YouTube channel – doesn’t necessarily share in those revenues. Which means for the label, YouTube itself needs to generate more income. Which means both labels and the video site need to capitalise on the advertising and brand partnership opportunities that the platform provides.

Even if the record company is cut into other artist revenues through multi-stream deals, again, both labels and YouTube have much work to do to fully capitalise on artist-based up-sell opportunities.

For Spotify, of course, the primary up-sell opportunity on its free level is turning freemium users into premium customers. True, Spotify could also be up-selling tickets and merch (and it has dabbled in this kind of up-sell), but really it wants to persuade people to become ten pound a month subscribers.

The record industry also wants this to happen, Spotify premium users being amongst its best customers in 2015. And while Spotify’s 1-in-4 up-sell rate is actually pretty impressive, the labels would like Spotify to be turning ever higher numbers of its free users into premium subscribers.

To date Spotify has promoted premium to freemium users with the promise of no ads and more mobile functionality. Though the former hinders the company’s ability to sell ads on the free level (you are basically asking advertisers to pay to inconvenience your listeners) and the latter, while a decent plus point, isn’t enough to persuade most free users to upgrade.

Many feel that keeping the most in-demand content off freemium – ie the biggest artists and latest in-demand releases – is probably the simplest way to differentiate free from paid.

Spotify has heavily resisted this approach to date, possibly not wanting to face the politics of having to decide which albums and artists qualify for the premium-only status. The DSP also points out that this will only work if labels ensure premium-only content isn’t freely available on-demand on YouTube.

Though, having seen its freemium level come under fire with increased frequency in the music community this year, it seems that Spotify will start dabbling with the hold-some-music-off-freemium approach in 2016.

However good you make Spotify premium, the issue remains that for most consumers £120 a year for recorded music is simply too high a price. As no one wants to cut prices across the board, to tackle this problem the industry needs to offer some mid-price alternatives that offer less content or functionality than the ten pounds a month package, but more than freemium.

Quite what the £2 and £5 a month premium services look like remains a key question in digital music. Which brings us to challenge number five…

5. DEVELOPING A BETTER RANGE OF SERVICES

The record industry – usually when countering the “bloody luddite labels” allegation – likes to point out the long list of digital services it has licensed. “Look how innovative and forward looking we are”, they imply.

It’s true, a lot of digital services have now been licensed, both in the UK and worldwide, though the vast majority are operating one of three business models: the iTunes model, the Pandora model or the Spotify model. Most have pretty much the same catalogue and charge pretty much the same price (in any one market). Rival services compete on user-interface and discovery tools or – actually, in commercial terms – often on how many mobile bundling deals they can negotiate.

The Spotify model is the one that is in rapid growth, in terms of users and revenue, but – as we said – realistically the £120 a year price point will only ever appeal to a minority audience, even if it’s a lucrative minority. What we now need are lower-priced subscription set-ups, that offer less than Spotify, so they don’t compete with the £120-a-year services, but can turn casual music consumers into paying subscribers.

Digital start-ups will say that labels and publishers won’t license innovative mid-price products. Labels and publishers will say that their hands are tied by Spotify – a key business partner – but one locked to its freemium-sells-premium business model.

Spotify freemium is arguably too good, making it hard to launch mid-price products that have decent unique selling points without being too close to Spotify premium. Spotify will say that it needs a compelling freemium level to hook-in new customers, and that it can’t cut back on its freemium package while YouTube’s free offer is so good.

The labels and publishers will say that they can’t do anything about bloody YouTube because of the bloody safe harbours in copyright law, which the video site exploits. So they tell their lobbyists to argue for a rewrite of copyright law in Brussels and Washington, meaning the future of the streaming music market now relies on a political battle the music industry will probably lose.

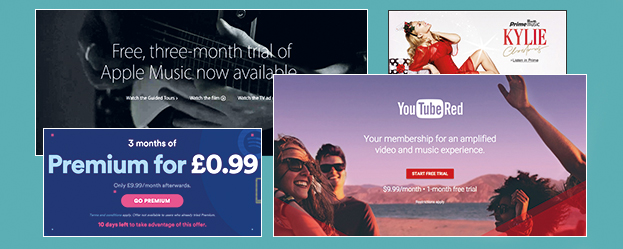

So what next? Well, ironically, while all that has been going on, YouTube – with its new subscription service Red – might have already kickstarted the next stage of streaming music’s evolution. Though, YouTube-haters might like to know, Amazon got there first by adding music to its Prime package.

Because providing a better range of streaming services for consumers might be less about launching the £2 streaming music platform, and more about bundling music in with other forms of entertainment for which, when put together, mainstream consumers are willing to spend ten pounds a month, or thereabouts.

LOOKING AHEAD

So, there we have it, the five big digital challenges the music industry faces in the next year, some internal challenges, some marketing-based, and others all about further evolving the streaming music market itself. To conclude, the questions the music industry needs to ask itself this new year are as follows…

• Is there anything we can do about the digital pie debate?

• Can better performer rights – and ‘equitable remuneration’ – protect artists?

• Will labels/publishers/CMOs get better at processing data/money?

• What can artists/managers do about the lack of transparency?

• Can artists/labels get better at marketing for streams?

• Can we make more money and/or better up-sell from free services?

• How can we ensure a better choice of streaming music services?

• Are bundled services really the future?