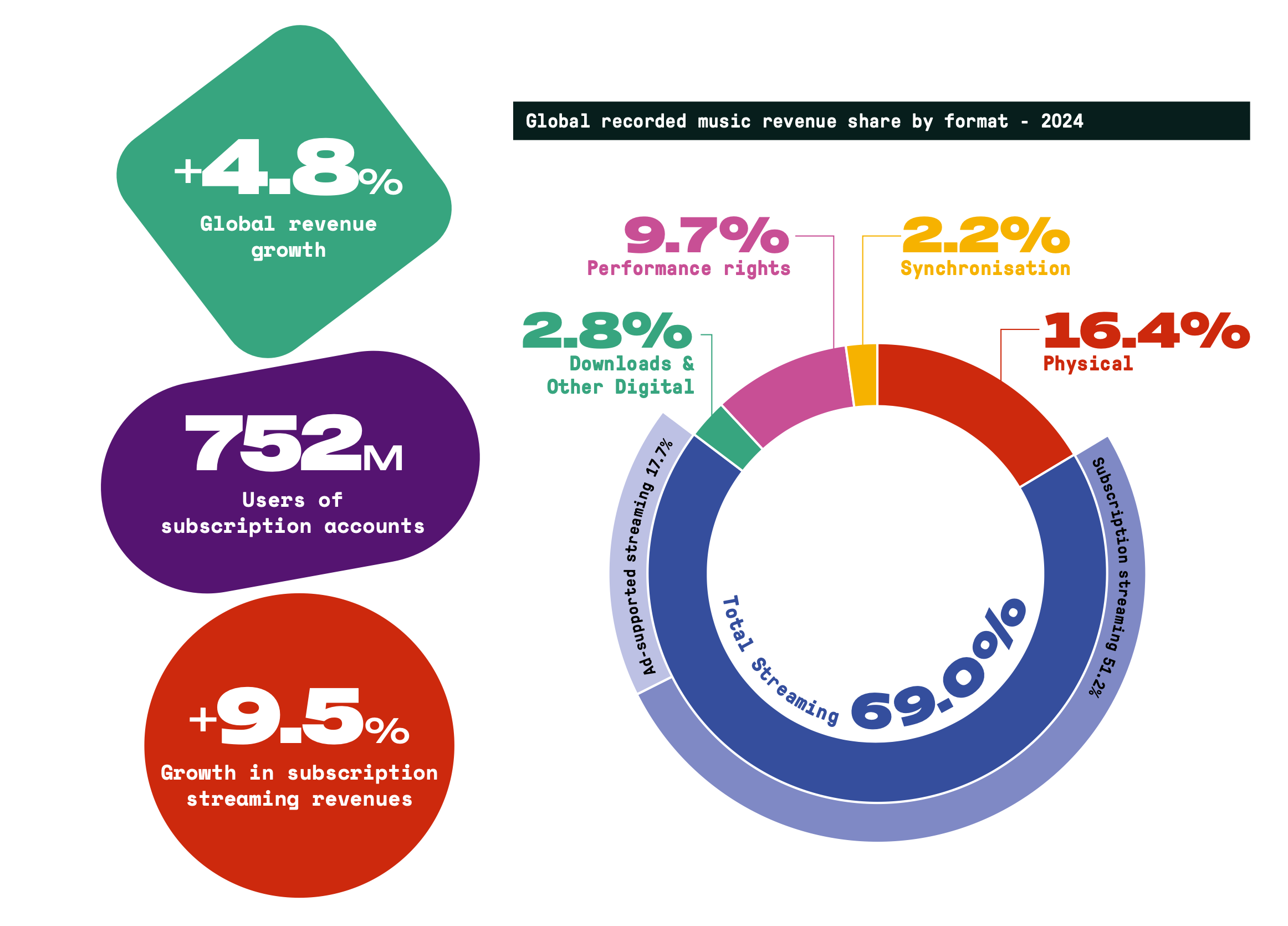

The global recorded music industry has notched up a tenth year of consecutive growth, with revenues rising 4.8% to hit $29.6 billion in 2024, according to IFPI’s ‘Global Music Report’, which was released yesterday.

While that headline figure - adding an apparently healthy $1.4 billion to the sector’s topline - looks impressive, the growth rate represents a significant deceleration, and pegs a full percentage point behind 2024’s headline global inflation figure, estimated by the International Monetary Fund to be 5.8%.

IFPI claims that there are now 752 million premium streaming subscribers across the world, up 10.4% from last year, with subscription streaming bringing in total revenues of $20.4 billion - up 9.5% from 2023. That equates - on a very blunt calculation - to roughly $27.13 in streaming revenue to the record industry per subscriber.

Spotify, of course, delivered a big chunk of that - both in terms of revenues and subscribers - with total revenues for 2024 reaching €15.673 billion, underpinned by 263 million premium subscribers by the end of 2024. Just under €11 billion of that revenue made its way back to rightsholders, though, of course, only a proportion of that - albeit the lion’s share - flows back to the owners of sound recordings.

In her first ‘Global Music Report’ presentation as IFPI CEO, Victoria Oakley gave her best attempt at a positive spin on the numbers - and in particular that slowing growth rate - acknowledging that this year’s figures represent “a slower rate of growth compared to last year and other years”, but that “many industries would be not just pleased with, but frankly quite jealous” of the record industry’s revenue growth.

Oakley notes that there is “still great potential for further development, through innovation, emerging technologies and investment in both artists and the evolving parts of the growing global music ecosystem”.

At a panel discussion launching the report, IFPI dug into what those evolving parts of the music system might look like, with Warner Music Canada’s Kristin Burke talking up the major’s cross-cultural collaborations and in particular the Ninety One North Records initiative connecting the Canadian and Indian music scenes.

“Canada is such a diverse society”, says Burke, “and we really have a vibrant, growing, South Asian music scene”. However, there “was not a lot of infrastructure in Canada to support this music scene”, she explains, adding that the label specifically recruited team members “of South Asian heritage, because they are really immersed in the music and in the culture” to work with a diverse roster of artists, targeting key diaspora markets, including the UK, Australia and the United Arab Emirates.

While streaming growth may be slowing down at a global level, Sub-Saharan Africa saw explosive growth of 22.6% in 2024, reflecting the region’s rapidly developing digital music ecosystem, with streaming playing a key role in bringing on previously under-served markets - a point articulated by Universal Music’s top banana Lucian Grainge on the major’s recent earnings call.

Mirroring those comments, Tega Oghenejobo, COO of Nigeria’s afrobeats label Mavin Global, in which UMG acquired a majority stake earlier this year, says that Africa is seeing growth because of smartphone penetration, driving streaming viability, which in turn creates a virtuous cycle for the region’s music industry, driven by streaming data and insights.

“It’s giving the labels on the ground, the A&Rs, the managers, more insights”, he explains. The increased level of data provided by streaming consumption enables local executives to “look at artists” with more confidence, spotting them when they are young, and enabling labels to “invest in them and put them in a position” where they can thrive “not just locally, but internationally”. This all, he notes, is driving more investment in Africa, not only from labels, but also ticketing companies and publishing houses.

That data-led development is not just happening in emerging markets, but is also having a dramatic impact on the evolution of artist development in developed markets, as streaming provides increasingly granular data on consumer behaviour. Warner Music UK’s Chief Operating Officer Isabel Garvey explained how the industry’s traditional metrics of success are extending far beyond traditional chart positions, with the industry becoming “more data-led than we’ve ever been before”.

However, this presents its own challenges, says Garvey, and requires sophisticated analysis to be useful. “The challenge is actually understanding the correlations and dependencies that help us generate artist and marketing success”, she notes. Current analytics efforts are focusing on “streaming velocity and engagement” rather than raw numbers, noting that “every stream is not created equal”.

The global nature of streaming has also transformed how labels track artist progress. “The world is completely borderless”, explains Garvey. “We’re not just looking at our home market, we’re looking international to understand trade routes and how to move artists through various territories and trends”.

Those trends include “metrics far beyond just the music”, she adds. “We look at live and we look at even how artists are influencing culture and social conversations”.

As a result, the industry is able to tap into more diverse paths to success, with labels and artists “co-designing what success looks like”, rather than working to traditional and standardised career trajectories.

Garvey points to two notable examples. “Fred Again.. has had one single in the top ten yet he’s selling out arenas in the US and Australia”, she says. “He’s kind of his own scene”.

Meanwhile, Charlie XCX’s big breakthrough came only at “album number six for her. She never tried to be mainstream. She followed her vision”. The label was, says Garvey, “patient with what she wanted to do, and lent into her vision of what success looked like for her”.

There are two areas highlighted in this year’s ‘GMR’ which, says Sony Music’s Dennis Kooker, are “areas for new businesses that are either currently under monetised or business models that don’t even exist yet” - gaming and AI.

Gaming, says Kooker, is - for “young consumers” under 25 - one of the “top two entertainment choices” alongside music, noting that “often those experiences can be complementary. It’s not one or the other”. However, Kooker adds, “the music experience needs to be more dynamic and persistent versus the typical way games integrate music”. If the gaming industry and music industry can crack that, “this will unlock opportunities to grow both the gaming and music experience hand in hand”.

RCA UK’s Stacey Tang pointed to Myles Smith’s Fortnite collaboration as a leading example of this. That collaboration “came about in about ten weeks”, says Tang, noting that “for anyone who works at a label or in creative, that’s pretty fast for making artwork”, let alone something of the scale of Smith’s in-game activation. Gaming is “like a new TV”, says Tang, with the additional benefit that Fortnite harnessed a “format that Myles excels in, in terms of storytelling and delivering his lyrics and his music to people”.

The creative challenges presented by new platforms can’t be ignored, notes Tang. “Within Fortnite, Myles performed the gig, but each scene had something different that was relevant to the emotion of the song and there was also a group activity that players could get involved in”, she explains. Giving fans an “exchange” when they are meeting an artist rather than being purely “transactional” means there’s a “deeper emotion” between fans and artists, which in turn allows labels to build a deeper understanding.

Inevitably, much of yesterday’s discussion was dominated by the music industry’s complex relationship with AI. That said, most of the initiatives under discussion have already been announced, and there was little that was new. Universal Music’s Cassandra Strauss pointed to the major’s “responsible AI initiative” which, she says “benefits artists, songwriters, rightsholders, the entire creative ecosystem”.

“At its best”, says IFPI boss Oakley, “generative AI can be a really powerful tool for artists and consumers alike”, but there is a significant threat from “developers of generative AI systems ‘ingesting’ copyright protected music to train their models without authorisation from rightsholders”.

Legitimate music licensing, says Kooker, is worth “probably in excess of $50 billion a year”, and is being put at risk by “those who are arguing for [copyright] exceptions”, by which he mainly means the big AI companies.

“Imagine being able to reduce or eliminate” that licensing cost to turn a profit, or “to be able to go and market your new music generation service so that you can put the existing players out of business whilst paying artists and songwriters nothing at the same time”.

That, says Kooker, is “an incredible market distortion”, and puts at risk the entire business model of the music industry. “Data is essential to training generative AI models”, he adds. “Without data there’s no product. It’s an essential cost of doing business, unless you’re able to convince governments to give it to you for free”.

The future of growth, says Kooker, needs to be via “paid subscription supported with a rights model that encourages free market deals, builds value for artists and songwriters, for music companies and publishers, and for DSPs who build great products while all delivering a product that consumers love”.

Whether that model will continue to deliver growth that will make other industries jealous is another question. Bloomberg predicts that the AI industry could grow at a compound annual growth rate of 42% over the next ten years; the market cap of Nvidia - a key stakeholder in AI technology that builds the chips that power much of the current innovation in AI - currently sits at nearly $3 trillion on revenues of $130 billion, up 114% year on year.

Meanwhile, Open AI is talking up an investment of $500 billion in AI infrastructure, and calling on Trump to rewrite copyright laws to favour AI companies, saying that the US should apply pressure to “less innovative countries” to get the same result.

With all those factors in play, the record industry may need to fight harder than ever to grow its $30 billion in revenues over the next decade.