This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends Digital Labels & Publishers Legal

Trends: Dancing babies, fair use and takedowns – Explaining Lenz v Universal

By Chris Cooke | Published on Monday 14 November 2016

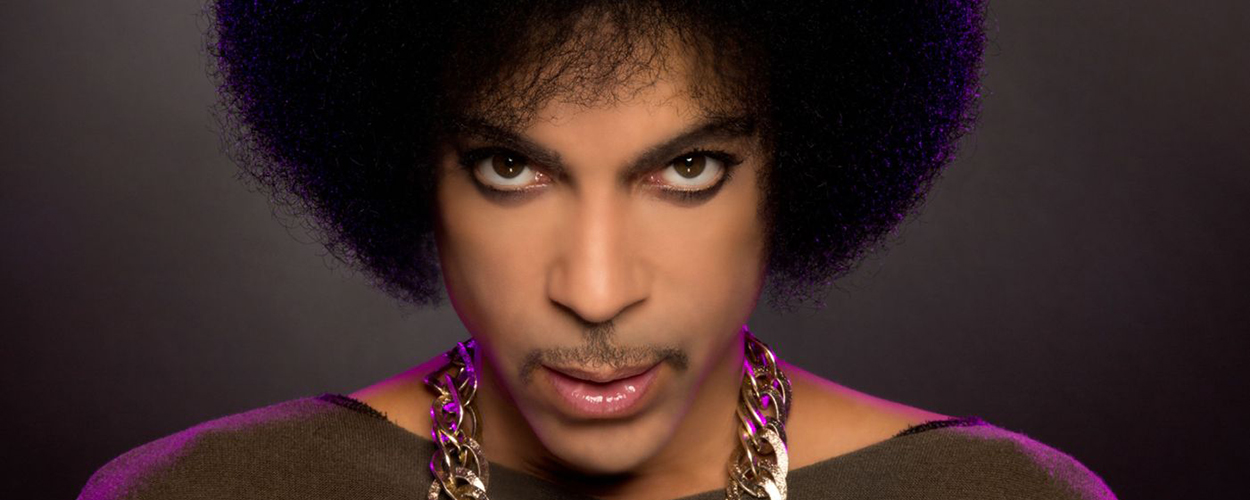

As Prince fans await with anticipation for the posthumous release of previously unheard recordings, a very long running piece of litigation involving a YouTube video that featured a snippet of the musician’s work could reach the US Supreme Court next year. But what is the so called ‘dancing baby’ case all about, what is this ‘fair use’ thing exactly, and why could a 20 second helping of a Prince track impact on the way rights owners have unlicensed content removed from the internet?

The event that kickstarted this whole legal debate occurred nearly ten years ago. In 2007, Stephanie Lenz posted to YouTube a video of her then thirteen month old son dancing to the 1984 Prince hit ‘Let’s Go Crazy’. Universal Music Publishing, as publisher of the song, issued a takedown notice, because the video used the work without permission, and YouTube duly blocked the video. However, Lenz claimed that the way the track appeared in her video was fair use under US copyright law, and demanded that YouTube reinstate the 30 second clip, which it subsequently did.

That might have been the end of it, except that Lenz, backed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, then argued that Universal should have recognised that her video constituted fair use of Prince’s song before issuing the takedown request, and that by failing to do so it had misused the takedown system provided by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Hence the ten years of legal wrangling that could as yet be due one final chapter in the Supreme Court in 2017.

WHAT IS FAIR USE?

The basic concept of copyright is that the law provides the copyright owner with certain controls over the creative works that they own. The exact list of controls varies from copyright system to copyright system, but commonly includes a reproduction, distribution, rental, adaptation, performance and communication control.

These controls mean that only the copyright owner has the automatic right to reproduce, distribute, rent out, adapt, perform in public or communicate to the public the content it owns. If anyone else wants to do any of these things with the piece of content, then they must seek permission from the copyright owner. The rights owner usually sells this permission, which is how copyright makes money.

However, having provided the rights owner with this handy list of controls, copyright law then often immediately limits at least some of them, or takes them away entirely in certain scenarios. For example, many copyright systems provide compulsory licences for certain uses of copyright work. Radio is often covered by such a licence. This means the copyright owner is obliged to give permission to certain sets of licensees in certain circumstances, usually charging rates set by statute, or a statutory body, or a court of law.

Then there are the copyright exceptions or exemptions. These are scenarios where third parties can make use of a copyright work without seeking a licence and without paying anyone any money. In much the same way the list of copyright controls varies from country to country, so does the list of copyright exceptions, though possibly more so.

Though a common copyright exception is the critical analysis exception. This exists for pragmatic reasons, and could be seen as the law trying to balance intellectual property and free speech rights.

The critical analysis exception basically means that someone can present a snippet of a copyright work without licence as part of a critique of that work. After all, if you had a movie review programme on TV, and that programme had to get permission from each movie studio to show a snippet of each film, the studio could say “will we get a positive review?”, and if the programme producer said “no”, they could refuse to license. To overcome that scenario there is a critical analysis exception. Though there are limitations on this exception, you can’t show the entire movie and then give it a 30 second review.

Another exception that seeks to balance intellectual property and free speech rights is the parody exception. In the UK this is a relatively new copyright exception, added in 2014.

It means that, for example, you can rework someone else’s song for humorous or satirical effect without getting permission from the song’s copyright owner, partly because the parody may be mocking the song’s creator or owner and they would therefore probably try to block the satirist’s work. Again, there are limitations on this exception, which vary from country to country; sometimes the parody has to be specifically lampooning someone connected to the original song for the exception to apply.

Not all exceptions relate to free speech, others apply where an individual wants to make use of a copyright work for an educational or non-commercial purpose, or often both.

For example, another common exception is the private copy right, which says that people who buy a legitimate copy of a sound recording can make further copies without licence providing they are for their own personal use.

This is an exception that is often accompanied by some sort of compensation system for the music community, usually a private copy levy applied to devices used to make the private copies (so originally blank cassettes and now sometimes smartphones). Recent attempts to introduce this exception into the UK failed because the government opted not to include such a levy, which the courts deemed breached European law.

As well as the list of exceptions varying from copyright system to copyright system, so does the name for these exceptions and the principles of exactly how they are applied. In so called common law systems, the term ‘fair dealing’ is often used to describe some or all of the exceptions, while in the US the term ‘fair use’ is applied.

Meanwhile, in some countries these exceptions are applied quite rigidly – the exception only applies in the specific circumstances outlined in copyright law – while other systems provide some flexibility for people wishing to plead fair dealing or fair use when accused of copyright infringement. Generally the US principle of fair use is much more flexible than the UK principle of fair dealing, which is why you have more debates about what is and is not fair use.

WHAT ARE TAKEDOWN SYSTEMS?

The takedown system employed by Universal to have Lenz’s video removed stems from the often controversial safe harbours in US copyright law, specifically the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

The safe harbours were designed to protect internet companies from being held liable for the unlicensed hosting or distribution of content across their networks by their customers; the argument being that if internet service providers and server hosting companies could be held liable for such copyright infringement, then the growth of internet service businesses would be curtailed.

The same safe harbours are used by YouTube – which is where much of the recent controversy about safe harbours stems from – so that Google cannot be held liable when users upload videos containing uncleared music to the YouTube website.

Safe harbour protection is dependent on the internet company providing some sort of system via which copyright owners can have infringing content – or links to such content – removed. The law is generally vague on exactly how these takedown systems should work, and some companies have developed much better systems than others. For all the controversy, YouTube’s Content ID system is probably one of the best.

Many rights owners are of the opinion that many internet companies provide inadequate takedown systems; sometimes possibly deliberately, because an internet company actually benefits from the pirated content its users upload. To this end the music and movie industries would like the law to be refined, so to increase the obligations of safe harbour dwellers with regards the takedown systems they operate.

On the flip side, some tech companies and users of websites like YouTube have argued that sometimes rights owners misuse takedown systems, by ordering content be removed that they don’t actually control, or which they only control in one territory, or which was actually covered by a licence somewhere along the lines.

The DMCA recognised that takedown systems may be misused in this way, and says that any rights owner that “materially misrepresents” that a piece of uploaded content is infringing when it is, in fact, not, could be liable to pay damages to the person who uploaded the content the rights owner sought to takedown.

THE ‘DANCING BABY’ CASE

Which brings us back to the ‘dancing baby’ case, which asked the question, in order to not “materially misrepresent” an alleged infringement, must an American rights owner first consider whether the unlicensed use of their work by a third party constitutes fair use under US law before issuing a takedown.

Lenz argued “yes”, and that because the 20 seconds of Prince playing in the background of her video was fair use, Universal misused the takedown system when it had the video blocked.

At each turn, Universal has argued that forcing copyright owners to consider the slightly ambiguous concept of fair use on every single piece of content uploaded to the internet that contains one of their works without permission would put an unrealistic burden on rights owners.

So while an uploader might subsequently successfully counter a takedown request by pleading fair use, there shouldn’t be an obligation on the rights owner to consider potential fair use claims at the outset.

The US courts – most recently the Ninth Circuit Court Of Appeals last year – have disagreed with the music major. Though in doing so, they have somewhat weakened the protection available to those who put up content online containing fair use of other people’s work.

The court says that rights owners, before issuing a takedown, must consider fair use – and properly, not just paying lip service to the concept – but if, having considered it, they then proceed with the takedown in “good faith”, then that’s fine. Which is to say, the assessment as to whether fair use applies need not be too rigorous.

To quote the Ninth Circuit last year: “To be clear, if a copyright holder ignores or neglects our unequivocal holding that it must consider fair use before sending a takedown notification, it is liable for damages”.

It added: “If, however, a copyright holder forms a subjective good faith belief the allegedly infringing material does not constitute fair use, we are in no position to dispute the copyright holder’s belief even if we would have reached the opposite conclusion”.

And finally: “[But] a copyright holder who pays lip service to the consideration of fair use by claiming it formed a good faith belief when there is evidence to the contrary is still subject to liability”.

Both sides appealed last year’s ruling. Universal mainly on a side decision about possible damages due for its alleged misuse of the takedown system, Lenz on the ambiguities as to just how much consideration a rights owner must give to fair use before issuing its takedown request, the Ninth Circuit ruling suggesting only a little.

The American Supreme Court has already refused to consider Universal’s appeal, but is still pondering over the latter point. To that end, at the end of last month the court asked America’s Solicitor General in the Department Of Justice for his opinion on this particular element of the whole safe harbour and takedown procedure as set out in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

That doesn’t mean that the Supreme Court will definitely consider the case, but it possibly suggests it is seriously considering doing so. Some reckon that a bit of intellectual musing over the intricacies of intellectual property would be an attractive distraction for a Supreme Court currently nervous about taking on big politically charged cases while they are one judge down; the appointment of a replacement for the late Antonin Scalia being caught up in political wrangling in Washington.

If it does take the case, Supreme Court judges might also consider another issue that the Ninth Circuit discussed but did not resolve.

Such is the incredible quantity of unlicensed content currently posted onto the internet each day, a lot of rights owners now use automated systems for issuing at least some of their takedown requests. How could an automated takedown system possibly consider something as nuanced as fair use?

The Ninth Circuit decided it didn’t need to rule on this point, because in the Lenz case a human being issued the takedown request. But without considering such automated takedowns, the precedent set in this case immediately runs into new issues.