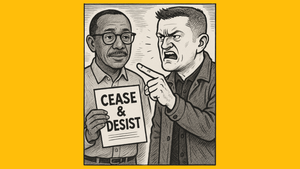

Singer-songwriter Labi Siffre and his publisher BMG have issued a cease and desist against right wing activist Tommy Robinson over his use of the hit song ‘(Something Inside) So Strong’ - a famous anti-apartheid anthem - on his social media and at the recent ‘Unite The Kingdom’ political rally in London.

Speaking to The Guardian, Siffre said, “Anybody who knows me and knows my work since 1970 will know the joke of them using the work of a positive atheist, homosexual black artist as apparently representative of their movement”. Robinson, real name Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, is “breaking all sorts of copyrights”, the musician went on, adding, “Even in an era when theft is easier than it ever was, it’s still theft”.

Former ‘X-Factor’ contestant Charlie Heaney sang Siffre’s song at the 'Unite The Kingdom' rally earlier this month, with Robinson reportedly introducing the performance by saying, “I always like telling stories through music and this next song now is going to tell all of our stories of why we’re here and why we care”. The right-wing activist has also reportedly included the song in social media posts.

Politicians using music in their videos, or at their events, without the explicit permission of the songwriters and musicians who created the song or track being used often causes controversy, particularly when those politicians promote controversial right wing opinions.

In the US, numerous artists have hit out at Donald Trump for using their music at his rallies, while in the UK it’s often music used around keynote speeches at the Conservative Party Conference that causes a backlash.

In copyright terms, with videos posted to social media things are usually straightforward, in that permission must be sought from the relevant copyright owners. Even where social media platforms have their own music licences, because those only cover user-generated content, and would not apply to politicians or political organisations.

With political events, things can be more complicated, because they are often covered by blanket licences issued to either political groups or the venues they use by the music industry’s collecting societies. However, there can be some important exceptions to those blanket licences with events that are overtly political.

A spokesperson for UK songwriter society PRS told CMU that, “politicians or campaign organisers seeking to use music during events such as party conferences, election campaigns or political rallies must obtain written permission from the relevant rightsholders”.

That would include any publishers with a stake in a song copyright, plus - if a recording is used - whoever controls the separate copyright in the recording, often a record label.

Once that permission has been secured, the event organiser must make sure they or their venue have a performance licence, which would usually be TheMusicLicence issued by the PPL PRS Ltd, the joint venture licensing entity owned by PRS and record industry collecting society PPL.

“PPL PRS regularly write to customers to remind them of their obligation to seek specific clearance for the use of music in association with a political event, including when we are notified of any use of music in a political context”, the PRS spokesperson added.

Where a political group is particularly controversial - which would include anything involving Robinson - most copyright systems, including UK copyright law, provide artists with a possible additional route to stop the use of their songs, by enforcing their moral rights, even if in theory a licence is available to cover a group’s event.

A key moral right is the ‘right of integrity’, which allows a creator to stop a derogatory treatment of their work, and that may well apply when music is employed by political extremists.

Beyond the legal arguments, it used to be that most politicians would stop using music if an artist objected for simple PR reasons - not wanting a public squabble with a popular and respected musician - though in the Trump era those on the right wing of politics generally don’t care about such things anymore.

That is increasingly the case, even when a politician or activist's use of a song seems entirely inappropriate - as with Robinson’s use of ‘(Something Inside) So Strong’, which has long been seen as a global anthem against apartheid, a message somewhat at odds with his political positions.

Whether that irony, or the copyright claims, will have any impact on Robinson remains to be seen.